Implementing Emulation Methods

We have now created our Emu struct and defined a number of variables for it to manage, as well as defined an initialization function. Before we move on, there are a few useful methods we should add to our object now which will come in use once we begin implementation of the instructions.

Push and Pop

We have added both a stack array, as well as a pointer sp to manage the CPU's stack, however it will be useful to implement both a push and pop method so we can access it easily.

impl Emu {

// -- Unchanged code omitted --

fn push(&mut self, val: u16) {

self.stack[self.sp as usize] = val;

self.sp += 1;

}

fn pop(&mut self) -> u16 {

self.sp -= 1;

self.stack[self.sp as usize]

}

// -- Unchanged code omitted --

}

These are pretty straightforward. push adds the given 16-bit value to the spot pointed to by the Stack Pointer, then moves the pointer to the next position. pop performs this operation in reverse, moving the SP back to the previous value then returning what is there. Note that attempting to pop an empty stack results in an underflow panic[^1]. You are welcome to add extra handling here if you like, but in the event this were to occur, that would indicate a bug with either our emulator or the game code, so I feel that a complete panic is acceptable.

Font Sprites

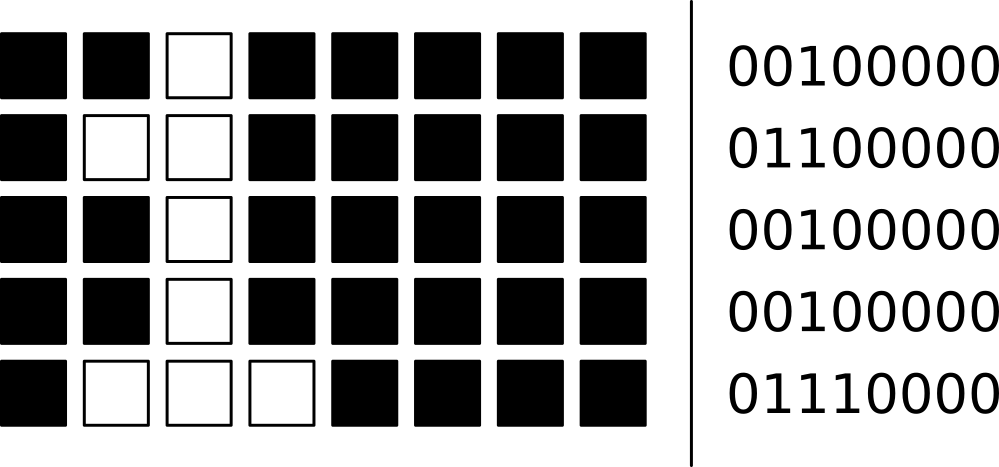

We haven't yet delved into how the Chip-8 screen display works, but the gist for now is that it renders sprites which are stored in memory to the screen, one line at a time. It is up to the game developer to correctly load their sprites before copying them over. However wouldn't it be nice if the system automatically had sprites for commonly used things, such as numbers? I mentioned earlier that our PC will begin at address 0x200, leaving the first 512 intentionally empty. Most modern emulators will use that space to store the sprite data for font characters of all the hexadecimal digits, that is characters of 0-9 and A-F. We could store this data at any fixed position in RAM, but this space is already defined as empty anyway. Each character is made up of five rows of eight pixels, with each row using a byte of data, meaning that each letter altogether takes up five bytes of data. The following diagram illustrates how a character is stored as bytes.

[^1] Underflow is when the value of an unsigned variable goes from above zero to below zero. In some languages the value would then "roll over" to the highest possible size, but in Rust this leads to a runtime error and needs to be handled differently if desired. The same goes for values exceeding the maximum possible value, known as overflow.

On the right, each row is encoded into binary. Each pixel is assigned a bit, which corresponds to whether that pixel will be white or black. Every sprite in Chip-8 is eight pixels wide, which means a pixel row requires 8-bits (1 byte). The above diagram shows the layout of the "1" character sprite. The sprites don't need all 8 bits of width, so they all have black right halves. Sprites have been created for all of the hexadecimal digits, and are required to be present somewhere in RAM for some games to function. Later in this guide we will cover the instruction that handles these sprites, which will show how these are loaded and how the emulator knows where to find them. For now, we simply need to define them. We will do so with a constant array of bytes; at the top of lib.rs, add:

const FONTSET_SIZE: usize = 80;

const FONTSET: [u8; FONTSET_SIZE] = [

0xF0, 0x90, 0x90, 0x90, 0xF0, // 0

0x20, 0x60, 0x20, 0x20, 0x70, // 1

0xF0, 0x10, 0xF0, 0x80, 0xF0, // 2

0xF0, 0x10, 0xF0, 0x10, 0xF0, // 3

0x90, 0x90, 0xF0, 0x10, 0x10, // 4

0xF0, 0x80, 0xF0, 0x10, 0xF0, // 5

0xF0, 0x80, 0xF0, 0x90, 0xF0, // 6

0xF0, 0x10, 0x20, 0x40, 0x40, // 7

0xF0, 0x90, 0xF0, 0x90, 0xF0, // 8

0xF0, 0x90, 0xF0, 0x10, 0xF0, // 9

0xF0, 0x90, 0xF0, 0x90, 0x90, // A

0xE0, 0x90, 0xE0, 0x90, 0xE0, // B

0xF0, 0x80, 0x80, 0x80, 0xF0, // C

0xE0, 0x90, 0x90, 0x90, 0xE0, // D

0xF0, 0x80, 0xF0, 0x80, 0xF0, // E

0xF0, 0x80, 0xF0, 0x80, 0x80 // F

];

You can see the bytes outlined in the "1" diagram above, all of the other letters work in a similar way. Now that these are outlined, we need to load them into RAM. Modify Emu::new() to copy those values in:

pub fn new() -> Self {

let mut new_emu = Self {

pc: START_ADDR,

ram: [0; RAM_SIZE],

screen: [false; SCREEN_WIDTH * SCREEN_HEIGHT],

v_reg: [0; NUM_REGS],

i_reg: 0,

sp: 0,

stack: [0; STACK_SIZE],

keys: [false; NUM_KEYS],

dt: 0,

st: 0,

};

new_emu.ram[..FONTSET_SIZE].copy_from_slice(&FONTSET);

new_emu

}

This initializes our Emu object in the same way as before, but copies in our character sprite data into RAM before returning it.

It will also be useful to be able to reset our emulator without having to create a new object. There are fancier ways of doing this, but we'll just keep it simple and create a function that resets our member variables back to their original values when called.

pub fn reset(&mut self) {

self.pc = START_ADDR;

self.ram = [0; RAM_SIZE];

self.screen = [false; SCREEN_WIDTH * SCREEN_HEIGHT];

self.v_reg = [0; NUM_REGS];

self.i_reg = 0;

self.sp = 0;

self.stack = [0; STACK_SIZE];

self.keys = [false; NUM_KEYS];

self.dt = 0;

self.st = 0;

self.ram[..FONTSET_SIZE].copy_from_slice(&FONTSET);

}

Tick

With the creation of our Emu object completed (for now), we can begin to define how the CPU will process each instruction and move through the game. To summarize what was described in the previous parts, the basic loop will be:

- Fetch the value from our game (loaded into RAM) at the memory address stored in our Program Counter.

- Decode this instruction.

- Execute, which will possibly involve modifying our CPU registers or RAM.

- Move the PC to the next instruction and repeat.

Let's begin by adding the opcode processing to our tick function, beginning with the fetching step:

// -- Unchanged code omitted --

pub fn tick(&mut self) {

// Fetch

let op = self.fetch();

// Decode

// Execute

}

fn fetch(&mut self) -> u16 {

// TODO

}

The fetch function will only be called internally as part of our tick loop, so it doesn't need to be public. The purpose of this function is to grab the instruction we are about to execute (known as an opcode) for use in the next steps of this cycle. If you're unfamiliar with Chip-8's instruction format, I recommend you refresh up with the overview from the earlier chapters.

Fortunately, Chip-8 is easier than many systems. For one, there's only 35 opcodes to deal with as opposed to the hundreds that many processors support. In addition, many systems store additional parameters for each opcode in subsequent bytes (such as operands for addition), Chip-8 encodes these into the opcode itself. Due to this, all Chip-8 opcodes are exactly 2 bytes, which is larger than some other systems, but the entire instruction is stored in those two bytes, while other contemporary systems might consume between 1 and 3 bytes per cycle.

Each opcode is encoded differently, but fortunately since all instructions consume two bytes, the fetch operation is the same for all of them, and implemented as such:

fn fetch(&mut self) -> u16 {

let higher_byte = self.ram[self.pc as usize] as u16;

let lower_byte = self.ram[(self.pc + 1) as usize] as u16;

let op = (higher_byte << 8) | lower_byte;

self.pc += 2;

op

}

This function fetches the 16-bit opcode stored at our current Program Counter. We store values in RAM as 8-bit values, so we fetch two and combine them as Big Endian. The PC is then incremented by the two bytes we just read, and our fetched opcode is returned for further processing.

Timer Tick

The Chip-8 specification also mentions two special purpose timers, the Delay Timer and the Sound Timer. While the tick function operates once every CPU cycle, these timers are modified instead once every frame, and thus need to be handled in a separate function. Their behavior is rather simple, every frame both decrease by one. If the Sound Timer is set to one, the system will emit a 'beep' noise. If the timers ever hit zero, they do not automatically reset; they will remain at zero until the game manually resets them to some value.

pub fn tick_timers(&mut self) {

if self.dt > 0 {

self.dt -= 1;

}

if self.st > 0 {

if self.st == 1 {

// BEEP

}

self.st -= 1;

}

}

Audio is the one thing that this guide won't cover, mostly due to increased complexity in getting audio to work in both our desktop and web browser frontends. For now we'll simply leave a comment where the beep would occur, but any curious readers are encouraged to implement it themselves (and then tell me how they did it).