Emulation Basics

This first chapter is an overview of the concepts of emulation development and the Chip-8. Subsequent chapters will have code implementations in Rust, if you have no interest in Rust or prefer to work without examples, this chapter will give an introduction to what steps a real system performs, what we need to emulate ourselves, and how all the moving pieces fit together. If you're completely new to this subject, this should provide the information you'll need to wrap your head around what you're about to implement.

What's in a Chip-8 Game?

Let's begin with a simple question. If I give you a Chip-8 "Read-Only Memory" (ROM) file, what exactly is in it? It needs to contain all of the game logic and graphical assets needed to make a game run on a screen, but how is it all laid out?

This is a basic, fundamental question; our goal is to read this file and make its program run. Well, there's only one way to find out, so let's try and open a Chip-8 game in a text editor (such as Notepad, TextEdit, or any others you prefer). For this example, I'm using the roms/PONG2 game included with this guide. Unless you're using a very fancy editor, you should probably see something similar to Figure 1.

This doesn't seem very helpful. In fact, it seems corrupted. Don't worry, your game is (probably) just fine. All computer programs are, at their core, just numbers saved into a file. These numbers can mean just about anything; it's only with context that a computer is able to put meaning to the values. Your text editor was designed to show and edit text in a language such as English, and thus will automatically try and use a language-focused context such as ASCII.

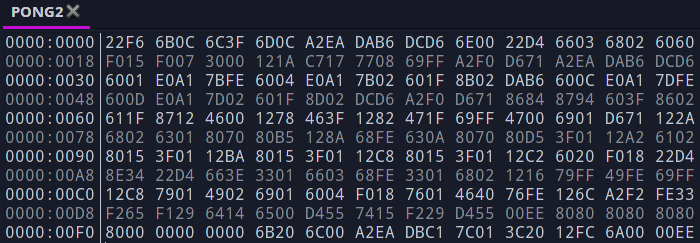

So we've learned that our Chip-8 file is not written in plain English, which we probably could have assumed already. So what does it look like? Fortunately, programs exist to display the raw contents of a file, so we will need to use one of those "hex editors" to display the actual contents of our file.

In Figure 2, the numbers on the left of the vertical line are the offset values, how many bytes we are away from the start of the file. On the right hand side are the actual values stored in the file. Both the offsets and data values are displayed in hexadecimal (we'll be dealing with hexadecimal quite a bit).

Okay, we have numbers now, so that's an improvement. If those numbers don't correspond to English letters, what do they mean? These are the instructions for the Chip-8's CPU. Actually, each instruction is two bytes, which is why I've grouped them in pairs in the screenshot.

What is a CPU?

Let me take a moment to describe exactly what functionality a CPU provides, for those who aren't familiar. A CPU, for our purposes, does math. That's it. Now, when I say it "does math", this includes your usual items such as addition, subtraction, and checking if two numbers are equal or not. There are also additional operations that are needed for the game to run, such as jumping to different sections of code, or fetching and saving numbers. The game file is entirely made up of mathematical operations for the CPU to preform.

All of the mathematical operations that the Chip-8 can perform have a corresponding number, called its opcode. A full list of the Chip-8's opcodes can be seen on this page. Whenever it is time for the emulator to perform another instruction (also referred to as a tick or a cycle), it will grab the next opcode from the game ROM and do whatever operation is specified by the opcode table; add, subtract, update what's drawn on the screen, whatever.

What about parameters? It's not enough to say "it's time to add", you need two numbers to actually add together, plus a place to put the sum when you're done. Other systems do this differently, but two bytes per operation is a lot of possible numbers, way more than the 35 operations that Chip-8 can actually do. The extra digits are used to pack in extra information into the opcode. The exact layout of this information varies between opcodes. The opcode table uses N's to indicate literal hexadecmial numbers. N for single digit, NN for two digits, and NNN for three digit literal values, or for a register to be specified via X or Y.

What are Registers?

Which brings us to our next topic. What on earth is a register? A register is a specially designated place to store a single byte for use in instructions. This may sound rather similar to RAM, and in some ways it is. While RAM is a large addressable place to store data, registers are usually few in number, they are all named, and they are directly used when executing an opcode. For many computers, if you want to use a value in RAM, it has to be copied into a register first.

The Chip-8 has sixteen registers that can be used freely by the programmer, named V0 through VF (0-15 in hexadecimal). As an example of how registers can work, let's look at one of the addition operations in our opcode table. There is an operation for adding the values of two registers together, VX += VY, encoded as 8XY4. The 8XY4 is used for pattern matching the opcodes. If the current opcode begins with an 8 and ends with a 4, then this is the matching operation. The middle two digits then specify which registers we are to use. Let's say our opcode is 8124. It begins with an 8 and ends with a 4, so we're in the right place. For this instruction we will be using the values stored in V1 and V2, as those match the other two digits. Let's say V1 stores 5 and V2 stores 10, this operation would add those two values and replace what was in V1, thus V1 now holds 15.

Chip-8 contains a few more registers, but they serve very specific purposes. One of the most significant ones is the program counter (PC), which for Chip-8 can store a 16-bit value. I've made vague references to our "current opcode", but how do we keep track of where we are? Our emulator is simulating a computer running a program. It needs to start at the beginning of our game and move from opcode to opcode, executing the instructions as it's told. The PC holds the index of what game instruction we're currently working on. So it'll start at the first byte of the game, then move on to the third (remember all opcodes are two bytes), and so on and so forth. Some instructions can also tell the PC to go somewhere else in the game, but by default it will simply move forward opcode by opcode.

What is RAM?

We have our sixteen V registers, but even for a simple system like a Chip-8, we really would like to be able to store more than 16 numbers at a time. This is where random access memory (RAM) comes in. You're probably familiar with it in the context of your own computer, but RAM is a large array of numbers for the CPU to do with as it pleases. Chip-8 is not a physical system, so there is no standard amount of RAM it is supposed to have. However, emulation developers have more or less settled on 4096 bytes (4 KB), so our system will have the ability to store up to 4096 8-bit numbers in its RAM, way more than most games will use.

Now, time for an important detail: The Chip-8 CPU has free access to read and write to RAM as it pleases. It does not, however, have direct access to our game's ROM. With a name like "Read-Only Memory", it's safe to assume that we weren't going to be able to overwrite it, but the CPU can't read from ROM either? While the CPU needs to be able to read the game ROM, it accomplishes this indirectly, by copying the entire game into RAM when the game starts up. Therefore, Chip-8 games have a maximum size of 4 KB, any larger and they can't be completely loaded in. It is rather slow and inefficient to open our game file just to read a little bit of data over and over again. Instead, we want to be able to copy as much data as we can into RAM for us to more quickly use. The other catch is that somewhat confusingly, the ROM data is not loaded into very start of RAM. Instead, it's offset by 512 bytes (0x200). This means the first byte of the game is loaded at start into RAM address 0x200. The second ROM byte into 0x201, etc.

Why doesn't the Chip-8 simply store the game at the start of RAM and call it a day? Back when the Chip-8 was designed, computers had much more limited amount of RAM, and only one program could run at a given time. The first 0x200 bytes were allocated for the Chip-8 program itself to run in. Thus, modern Chip-8 emulators need to keep that in mind, as games are still developed with that concept. Our system will actually use a little bit of that empty space, but we will cover that later.